Computers, Robots, and Erasure

How language about technology has erased women and dehumanized workers

What do you think of when you see the word “computer”? Do you think of a human?

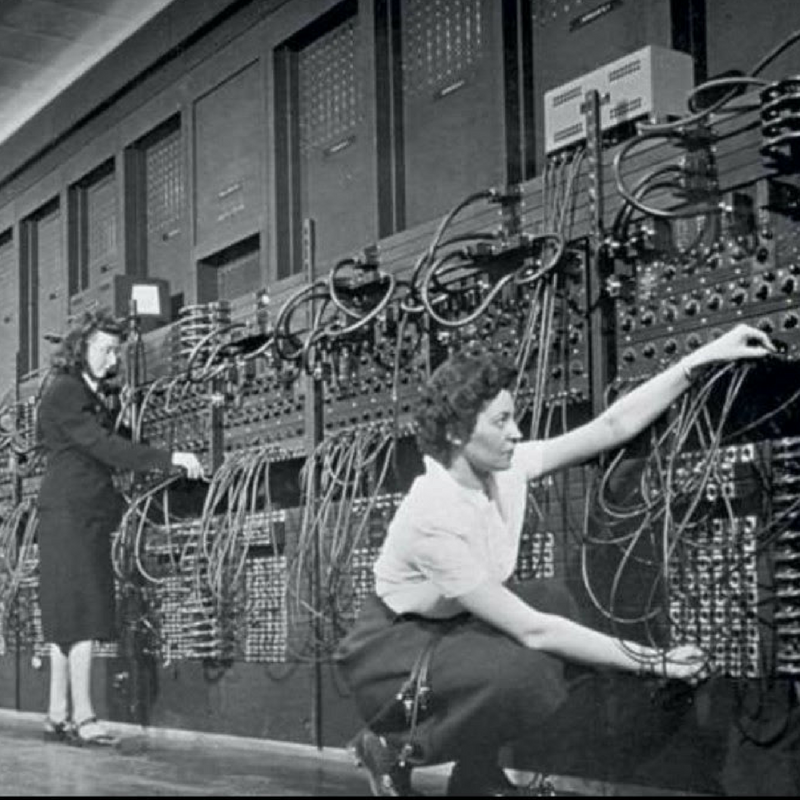

In the 21st century, the answer is obviously not; a computer is decidedly not a human. But at the beginning of the 20th century, you would. And, likely, you’d think of a woman:

In the mid-1950s, Kathleen Wicker received an assignment at work with one of the first electronic computers at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). “At the time, I hardly knew what a computer was,” she recalled in an interview 40 years later. “I thought it was a woman.”

Wicker’s statement might seem surprising today, but in the mid-twentieth century, the term “computer” referred to people, not machines. It was a job title, describing someone who performed mathematical equations and calculations, and NASA employed hundreds of women as “human computers” in this era.

So, in just about 50 years, the use of the word “computer” came to mean the opposite of a human.

What about the word “robot”? Do you think of a human?

In the 21st century among English speakers, the answer is again decidedly not a human. This, too, was a 20th century innovation:

Robot is drawn from an old Church Slavonic word, robota, for “servitude,” “forced labor” or “drudgery.” The word, which also has cognates in German, Russian, Polish and Czech, was a product of the central European system of serfdom by which a tenant’s rent was paid for in forced labor or service.

Today, in Russian, рабочий (pronounced “rabochee”) means “worker” and работа (pronounced “rabota”) means “work”. So, how did this eastern European word referring to manual labor (specifically serfs) come to mean the opposite?

It owes its origin to “a brilliant Czech playwright, novelist and journalist named Karel Čapek (1880-1938) who introduced it in his 1920 hit play, R.U.R., or Rossum’s Universal Robots.”

Taking its cues from other literary accounts of scientifically created life forms such as Mary Shelley’s classic Frankenstein and the Yiddish-Czech legend The Golem, R.U.R. tells the story of a company using the latest biology, chemistry and physiology to mass produce workers who “lack nothing but a soul.” The robots perform all the work that humans preferred not to do and, soon, the company is inundated with orders. In early drafts of his play, Čapek named these creatures labori, after the Latinat root for labor, but worried that the term sounded too “bookish.” At the suggestion of his brother, Josef, Čapek ultimately opted for roboti, or in English, robots.

In the play’s final act, the robots revolt against their human creators. After killing most of the people living on the planet, the robots realize they need humans because none of them can figure out the means to manufacture more robots a secret that dies out with the last human being. In the end, there is a deus ex machina moment, when two robots somehow acquire the human traits of love and compassion and go off into the sunset to make the world anew.

Audiences loved the play across Europe and the United States.

In 100 years, robots went from human laborers at the bottom of the social order to being literally inhuman.

Beyond being etymologically interesting that the words “computer” and “robot” have had their meanings inverted, I can’t help but wonder about the throughline: that the altered words had the effect of erasing and dehumanizing the labor of women and workers.

I also can’t help but wonder whether the early 20th century fear of a robot rebellion in the United States echoes the late 18th century fears of slave revolts in the United States.

All of which raises the question of what words do we use today to refer to humans that will mean the opposite 100 years from now? For example, consider modern-day anxieties around artificial intelligence. Already we have seen how “neural networks”, which just a few years ago would automatically evoke human brains, have become commonly associated with machine learning and automation.

It’s also worth considering what an alternative history might have been where, instead of the language of technology being deployed to erase the contributions of women and workers and replace humans, our language evolved in a way that elevated their humanity.

In writing this, I wish I had a slightly stronger thesis about what it is about our culture that caused these two specific inversions, and a stronger suggestion about how to properly think about them. But in the meantime, it’s worth reflecting on the power of words, even as they change over time.