Joining 18F

Why I'm leaving the greatest job in the world for another one

Today, I informed the members of the Council and my colleagues that I will be leaving the District government at the beginning of March and joining the growing ranks of public servants at 18F. One question I have heard from friends, colleagues, and family is “Why?” It’s a fair question. Those who know me know that I love my job: my staff is amazing, the work is fascinating, and I have been given extraordinary opportunities to serve the District of Columbia. So what gives?

Something Special is Happening

The second question I get from some of my friends is “What the hell is 18F?” I usually answer with variations of: “it’s an effort within the General Services Administration to remake the way the federal government builds and buys digital services.” After inevitable glazed eyes or–worse–dubious stares, I make a reference to <healthcare.gov> and depending on their interest level, I explain that 18F is trying to prove that government IT does not have to be terrible, that it can actually be good and user friendly.

But, upon reflection, that’s the wrong answer. 18F–from the outside anyway–appears to be two things. First, it is a modern-day digital skunk works. It has some of the best and brightest developers in America, building applications that agencies need in a modern, experimental, and explicitly iterative manner. The first Skunk Works led to, among other things, the creation of the U-2, the SR71 Blackbird, the Stealth Fighter, and more. These things were not the bread and butter of the U.S. Air Force’s day-to-day operations, but they contributed enormously to the United States’ air superiority. The original Skunk Works had, uh, flexible procurement concepts,1 and apparently was guided by the mantra: “quick, quiet and quality.”2

So, 18F is a modern-day digital skunk works. But it also another important thing. It is a digital maven.

Whether it is the work of Leah Bannon, Gray Brooks, and others to help agencies build out better APIs. Whether it is the work of Eric Mill to help agencies implement HTTPS on .gov domains. Whether it is the work of 18F Consulting to help agencies reimagine their procurement processes. 18F is at the vanguard of digital services for government.

And what’s more is that 18F is committed to building tools the Right Way: using and contributing to open-source tools, focusing on removing restrictions to public licensing and terms and conditions where appropriate, and being accountable to the public about the office’s work.

In short, something special is happening at 18F.

The Challenges are Real

The third question I get is “But Dave, don’t you love being a lawyer?” Yes. I do. But I love being a lawyer because (a) I genuinely love helping my clients solve their problems, even problems they never realized they had, and (b) lawyers (or at least the ones I have chosen to work closely with) want to promote justice, even when it is inconvenient. You don’t need to be a lawyer to love solving clients’ problems. But on the second reason, American lawyers have a rich tradition of using the law to advance the causes of equality, of working to ensure due process is not only available to the popular or wealthy, and of demanding more from their clients than mere compliance with the letter of the law. Government lawyers especially, in my experience, are deeply committed to serving the public and ensuring that our democratic institutions live up to their potential.

Yet, although there is much hand-wringing about the future of the practice of law, I am convinced that digital technology will be an important part of it. And, to me, a burning question is whether government lawyers will have the benefit of this technology or not. I have personally used the miserable technology that government attorneys use, and I know that–in some circumstances–I lacked the ability to provide counsel as well as I would want to because I lacked the resources to research, prepare, and review legal documents.

And, if we’re being honest, it’s not just lawyers who are stuck in the equivalent of a digital stone age. According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, legacy IT systems make up $54 billion, representing nearly 70% of federal IT budgets. It’s bleak.

We need Lawyers to Help

So, in my estimation, we need lawyers to help fix this. “Huh”, you’re thinking. Well, here’s the deal: it’s easier to teach lawyers about code then it is to teach coders about law. No, it’s not because lawyers are smarter than developers. It’s because developers have been working for decades to reduce barriers to entry and make systems easier and faster and more user-friendly. Lawyers… well… haven’t.

If we want government to fix its IT, scaling up is easier if lawyers and developers learn from each other. That’s because many of the barriers to technology adoption are legal in nature. Whether it’s statutory compliance, or licensing, or procurement, or appropriations, lawyers are an essential part of a government office. And although I will not be in the Office of General Counsel at GSA, I hope to be an intermediary for developers and lawyers. More importantly, I hope to bring a lawyer’s sense for solving clients’ problems, under duress, and under the totally legitimate, yet often frustrating, microscope of public scrutiny on government employees.

Conclusion

This career move is an exceptionally difficult one for me personally. Although I have been so amazingly fortunate at the Council and it will be hard to walk away, I am eager to tackle on the challenges at 18F and to join the incredible team there. I know that the new challenges will be stark; we will not fix all the things over night.

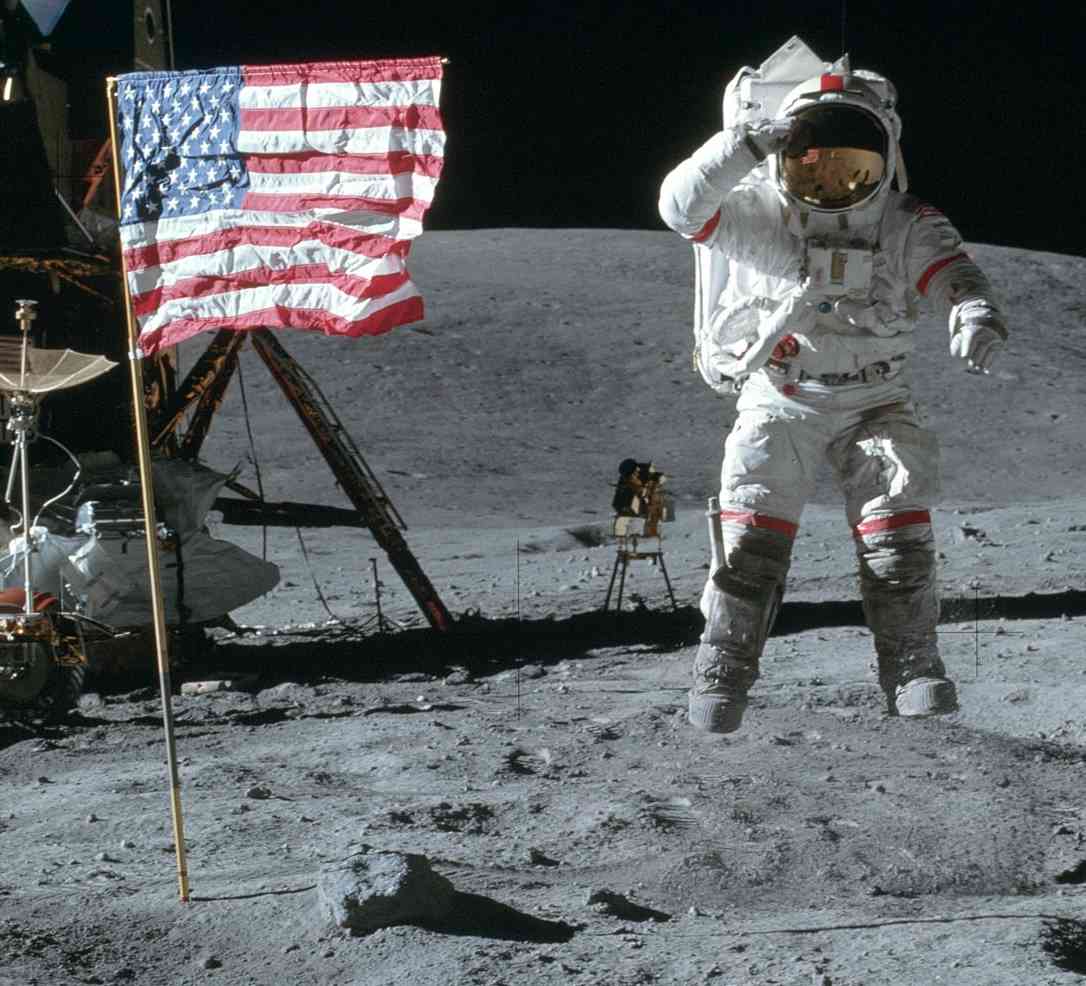

But, as JFK explained in his famous moon speech: “We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others, too.”

On the 50th anniversary of the moon landing four years from now, I hope to play a small part in ensuring that America is as hopeful for our future as we were when we made one giant leap for mankind.

“The formal contract for the XP-80 did not arrive at Lockheed until October 16, 1943; four months after work had already begun. This would prove to be a common practice within the Skunk Works. Many times a customer would come to the Skunk Works with a request, and on a handshake the project would begin, no contracts in place, no official submittal process.” http://www.lockheedmartin.com/us/aeronautics/skunkworks/origin.html ↩︎

http://www.lockheedmartin.com/us/aeronautics/skunkworks.html ↩︎