Court Statistics: Part I

Why we may need to open a "floodgate" of judicial data

This weekend, I spent approximately 16 hours sitting in a windowless meeting room in a Chicago hotel discussing specific processes for arbitrating family-law disputes. This is how Uniform Law Commissioners like me get our kicks.

During the weekend, I learned of a recent article entitled Let’s Stop Spreading Rumors About Settlement and Litigation: A Comparative Study of Settlement and Litigation in Hawaii Courts, written by one my fellow commissioners, the multi-talented Elizabeth Kent and her co-author John Barkai.

Based on this article, I plan on writing three blog posts about judicial data and, hopefully, make the case for lawyers and the courts to think more critically about the need for good judicial data.

Trial by Jury - Chaos in the Courtroom by David Henry Friston [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

“95% of all cases settle” == FALSE

The article starts with debunking a common misconception, even among lawyers who know it can’t possibly be true: that 95% of all civil cases settle. The data show that, in fact, about 70% of cases settle. And, if you remove tort cases, that number dips to about 40-60% of cases settle.

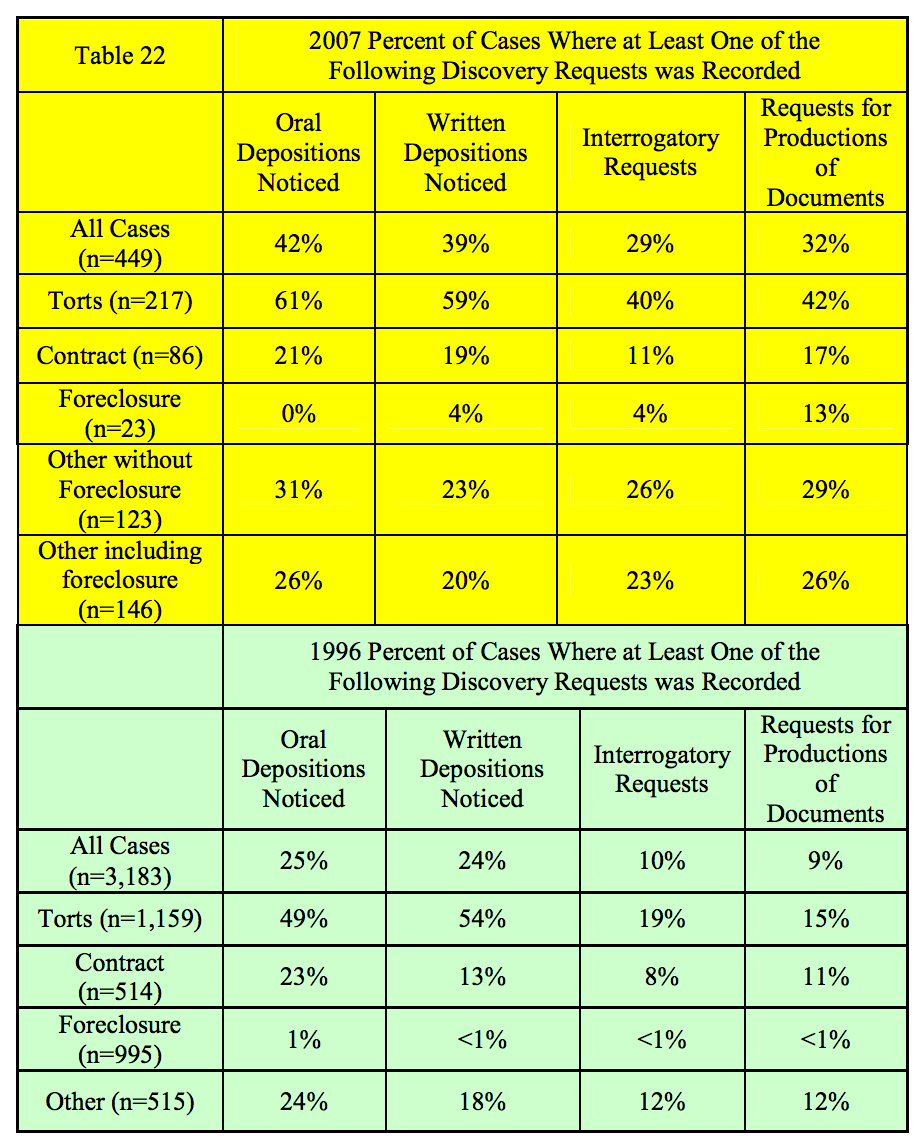

The article’s authors conducted two empirical studies–one in 1996 and one in 2007–concerning civil litigation and settlement in the Circuit Courts of Hawaii. The abstract, which is worth reading in full, explains that the data “comes from docket sheets of 4,000 cases, surveys of 500 lawyers, and court annual reports” and evaluates “the docket, the types of cases, the pattern of filings, the number of trials, the types of pretrial dispositions other than settlement, the settlement patterns, lawyers’ satisfaction with the settlements, the types of negotiations, the use of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) methods, events impacting settlements, the frequency of judicial assistance with settlements through court-scheduled settlement conferences, disposition time, the amount of pretrial discovery, and the demographics of the lawyers.”

The Abstract also identifies some important “highlights”:

Over 75 percent of cases that settle, settle without judicial assistance, and about one-half of the cases had no appearances before a judge. Over 90 percent of lawyers are satisfied with both their settlement terms and the settlement process. The most common type of negotiations is telephone negotiations, not face-to-face negotiation, which is the primary method of teaching negotiation in law schools. Telephone negotiations were the event with the greatest impact on settlement. Over 40 percent of cases used some form of ADR process. Multiple settlement events took place in the majority of cases where there was settlement activity. There was a great variance in the amount of pretrial discovery. Almost 50 percent of cases showed no pretrial discovery. Almost 85 percent of the lawyers surveyed had served as an arbitrator, and more than one-third had served as a mediator.

Empirical research such as this can be vitally important to understanding the practice of law. Such research provides lessons for legal educators, the courts, and practicing lawyers.

In the academy, the data should cause law schools to rethink how they teach negotiation. If phone negotiations and multi-stage negotiations are not only common, but also are effective, emphasizing face-to-face negotiation in law school misses the opportunity to prepare lawyers for practice.

In the courts, the data may cause courts to evaluate and calibrate the degree to which judicial settlement conferences and mandatory mediation should be used. Among the remarkable findings is this: “pretrial conferences” had a significantly greater impact on settlement in 2007 compared to 1996. Another is that cases were more likely to settle contemporaneously to a judicial proceeding in 2007 compared to 1996. It would be interesting to know if these trends are true throughout the states and, if so, why.

Data on discovery’s impact on settlement.

The data also confirms that discovery played a bigger role in 2007 than it did in 1996. Courts should be looking closely at their rules to see whether discovery and scheduling practices are more or less likely to result in successful alternative dispute resolution.

Importantly, the data should cause practicing lawyers to confront certain realities about litigation: resolution through alternative-dispute resolution is not as frequent as we might think. A phone call is more than twice as likely to lead to settlement compared to any other “settlement event.” Having the parties present during a face-to-face settlement negotiation appears to be far more effective than having a settlement negotiation without the parties in the room.

True, this is just one article, with unique characteristics for the jurisdiction. But the findings are nonetheless important and rigorous discussions about data in the legal profession can get better results for clients.

Ultimately, I know many people went to law school to avoid math, but data matters. And, in the next post, I will spend some time evaluating some comparable data in the DC courts.